$3,029.95

$2,729.95

$300

$2,425.00 | $2,725.00

$300

$2,135.00 | $2,435.00

$215.05

$799.95 | $1,015.00

$1,329.95

$1,329.95

$150

$1,645.95 | $1,795.95

$39.95

$299.00

$499.00

$29.95

$33

$626.00 | $659.00

$2,729.95

$3,029.95

$1,329.95

$34.95

$34.95

$34.95

$34.95

$34.95

$39.95

$39.95

$30

$669.95 | $699.95

$200

$1,649.00 | $1,849.00

$64.95

From

$95.00 | $159.95

$200

$2,299.00 | $2,499.00

$44.95

$5.00 | $49.95

$31

$119.95 | $150.95

$15.95

$90.00 | $105.95

Low Price

$8.95

$161.00 | $169.95

Low Price

$12.95

$23.00 | $35.95

$28.95

$161.00 | $189.95

Low Price

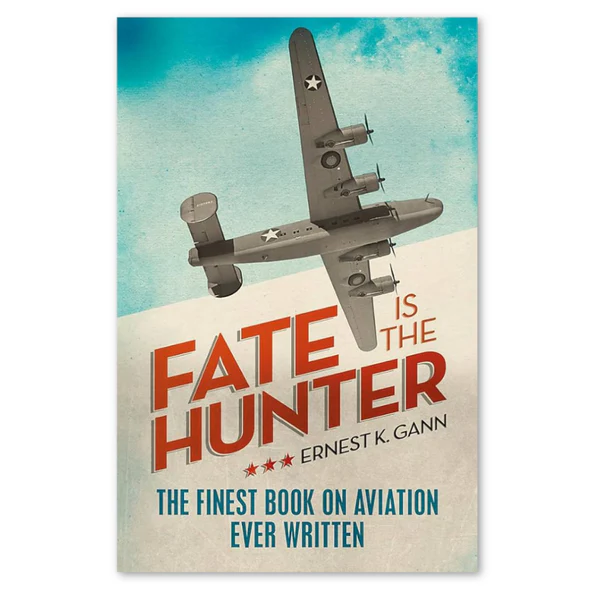

The copper-bottomed classic from a memorable and courageous pilot.

FATE IS THE HUNTER is a fascinating and thrilling account of some of the more memorable experiences Ernest K Gann had in the air. He's flown in both peace and war and come close to death many times. Here he reveals the characters he's known and the dramas he's experienced, portraying fate (or death) as a hunter constantly in pursuit of pilots. This is a fabulous account of both the history of aviation and one man's life in the air.

Ernest K. Gann’s classic pilot's memoir is an up-close and thrilling account of the treacherous early days of commercial aviation. “Few writers have ever drawn readers so intimately into the shielded sanctum of the cockpit, and it is hear that Mr. Gann is truly the artist” (The New York Times Book Review).

“A splendid and many-faceted personal memoir that is not only one man’s story but the story, in essence, of all men who fly” (Chicago Tribune). In his inimitable style, Gann brings you right into the cockpit, recounting both the triumphs and terrors of pilots who flew when flying was anything but routine.

Editorial Reviews

"Mr. Gann is a writer saturated in his subject; he has the skill to make every instant sharp and important and we catch the fever to know that documentary writing does not often invite." -- V.S. Pritchett ― New Statesman

"This book is an episodic log of some of the more memorable of [the author's] nearly ten thousand hours aloft in peace and (as a member of the Air Transport Command) in war. It is also an attempt to define by example his belief in the phenomenon of luck -- that 'the pattern of anyone fate is only partly contrived by the individual.'" -- The New Yorker

"Few writers have ever drawn their readers so intimately into the shielded sanctum of the cockpit, and it is here that Mr. Gann is truly the artist." -- New York Times Book Review

"Fate Is the Hunter is partly autobiographical, partly a chronicle of some of the most memorable and courageous pilots the reader will ever encounter in print; and always this book is about the workings of fate. . . . The book is studded with characters equally as memorable as the dramas they act out." -- Cornelius Ryan, author of A Bridge Too Far and The Longest Day

"This fascinating, well-told autobiography is a complete refutation of the comfortable cliché that 'man is master of his fate.' As far as pilots are concerned, fate (or death) is a hunter who is constantly in pursuit of them. . . . There is nothing depressing about Fate Is the Hunter. There is tension and suspense in it but there is great humor too. Happily, Gann never gets too technical for the layman to understand." -- Saturday Review

"This purely wonderful autobiographical volume is the best thing on flying and the meaning of flying that we have had since Antoine de Saint-Exupéry took us aloft on his winged prose in the late 1930s and early 1940s. . . . It is a splendid and many-faceted personal memoir that is not only one man's story but the story, in essence, of all men who fly." -- Chicago Sunday Tribune

About the Author

Ernest K. Gann is the author of numerous books, among them The High and the Mighty, Twilight for the Gods, The Aviator, and The Magistrate. He lives in Anacortes, Washington, and continues to write and publish prolifically.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter I

THE INNOCENTS

AND OF THE FACTS OF AERIAL LIFE

In the beginning many of us were scientific barbarians. We had neither the need nor the opportunity for technical culture. The interior of a cloud was a muggy and unpleasant place. We knew only that to penetrate cloud for any extended period of time was inviting trouble we were ill equipped to meet. Though we had long delighted in playing about the edges of cumulous battlements, we stayed on the ground when we could not see. Night flying was also a limited indulgence, if only because the fields from which we operated were the most humble in every respect and nothing about them, including the inevitable high-tension wires, was ever illuminated.

Thus, unlearned, credulous, and bewildered, certain of us emerged from the lower strata of aerial society. We had not been trained by the army or the navy and consequently occupied a social position roughly equivalent to that of a Hindu untouchable. Many of us still had that unremovable grime beneath our fingernails which could only have come from working on our own engines.

Our chief item of costume in this strange new world was the familiar, much-faded and much-loved leather jacket. We clung to them pathetically, for they were the last tangible evidence of a more carefree life. Our natural pride did not cover the fact that we were the most uncouth neophytes. Many of us still moved our lips as we plowed through the books and brochures designed to raise us higher in our chosen profession.

We are in a cheerless classroom. In the adjoining hangar a mechanic is pounding on a piece of metal. A man named Lester frowns upon our bumpkin manners. His open disapproval is repeated in the dour face of McIntosh, who serves as his assistant inquisitor.

Lester is a man whose face is not his own but a hodgepodge repair job which at least complements his patched-up body. Only a few years before, he was taking off from Rochester in a Stinson "A," a ship which had three engines, one in the center. Somehow he caught a wing tip on the snowbank which paralleled the runway. The Stinson cartwheeled. When the debris was finally torn away Lester was an integral part of it; so much so that it was nearly impossible to separate his vitals from the still-smoking center engine. It was said that every major bone in his body was fractured in one fashion or another and that his chances for survival in any form more interesting than a vegetable were nil.

The experts did not count upon Lester's magnificent courage and determination. He survived, if not truly to fly again, then to teach others the refinements demanded of an airline pilot.

We stand huddled together as Lester appraises us with his soul-chilling blue eyes. To please him is important, for it means eventual confirmation in our new positions. To fail means a certain return to the wilderness and the semistarvation of itinerant flying. Hence we are nearly terrified of this man who appears so frail as to seem almost translucent. And he soon proves not of the sort to soothe our fears.

Staring at us one by one, he paces the classroom like a great long-legged bird, wounded in body and grievously offended in spirit. His long thin hands pinch frequently at his broken nose. His voice is high pitched, almost a whine, as he calls the roll. He pronounces each name with open distaste, as if he has just bitten into a rotten persimmon.

"Gay, Lippincott, Sisto, Watkins, Mood, McGuire, Owen, Charleton, Carter..."

We confirm our presence solemnly, each of us unable to resist imitating the nervous monotone of the man before. McIntosh, gloomy-eyed, his thoughts impenetrable, lurks near the large aerial map on the wall. He puffs gently on an enormous pipe and, ignoring us completely, seems rapt in a streak of mud along one of his shoes.

Lester moves into the pale January light from the window, and the collection of freckles spotting his face and neck suddenly takes on a brilliant hue, emphasizing the parchmentlike texture of his skin. He begins by setting us very firmly in our places.

"You are supposed to know how to fly or you would not be here. You will now learn to fly all over again. Our way. I have examined your logbooks. They contain some interesting and clever lies. If you are lucky and work a good solid eighteen hours a day in this school, it is barely possible that a few of you may succeed in actually going out on the line -- that is, if the company is still in such desperate need of pilots that it will hire anybody who wears wings in his lapel and walks slowly past the front door.

"However --" he sighs -- "mine is not to reason why. Just remember, you were hired on a ninety-day probation clause. To begin with, you are going to know every damn..."

The lecture on our shortcomings and the penances to be assigned continues for the better part of the morning. The requirements seem overwhelming. In six weeks we must pass severe examinations in air mass analysis, instrument flight, radio, hydraulics, maintenance, company procedures, routes, manuals, forms, flight planning, and air traffic control. Not only the company but a government inspector will check our final grades.

Lester drones on, pausing only occasionally to crack the knuckles of his talonlike fingers. I study the others, curious about my fellow unwashed who have come from flying fields all over the land. They are strangers still, and I wonder if their natural cocksureness, without which they could never have survived to reach this room, is being as thoroughly squashed as my own.

With Gay I am the most familiar. We share a room in the cheap, musty hotel where we are supposed to live and study during the period of our incubation. He is younger than I am, of dark complexion, very handsome, and most generous with his magical smile. He has come from a small field in Tennessee where he instructed and on Sundays flew passengers for a dollar a ride.

Lippincott is immensely eager. His alertness is almost offensive, and it is already apparent that he will have little difficulty in mastering the engineering aspects which Lester has emphasized so much, to my own despair.

Sisto, a hoarse-voiced enfant terrible from somewhere in California, seems defiant, even bold enough to prod Lester with questions.

I have spoken to Owen only as we gathered, and I was then astounded at the basso-profundo voice emerging from so slight a young man.

Mood and McGuire have also come up from the South, and the contrast between them is a measure of the group. For absolutely no reason, I have already taken a dislike to Mood and I am certain he regards me with equal antipathy. McGuire, however, endeared himself at once by confessing both homesickness for the sight of a Carolina mule and claiming his head is composed almost entirely of bone and therefore a poor receptacle for all that Lester demands. His face now, as he listens to Lester, is so chiseled in honest planes of concentration it would please the most finicky sculptor. I have learned only that hitherto he was mostly engaged in crop dusting -- a chancy way to earn a living with wings.

Carter, large and red-faced, is propped audaciously and yet aloof against the back wall of the classroom. I do not know where he calls home, if indeed he has any in the usual sense. He must be a much-traveled man, for just beneath his shirt cuffs, encircling both wrists with intricate design, are the beginnings of what must be vast and elaborate tattoos. I am very impressed with anyone who can so absolutely disregard convention.

Charleton is a silent enigma, not having spoken so much as a word to any of us since first meeting. His face is kindly, although his eyes lack sparkle. His hair is prematurely gray and he seems very tired.

Peterson is a thin and hungry-looking man, slow-spoken and droll, and thus already much valued as a companion. Now straddling a bench, he looks like the reincarnation of Ichabod Crane.

Watkins is near him, sprawling in his seat as if even Lester could never alert him. He is very tall and in his debonair manner seems to patronize the gaunt figure pacing before him. He drums softly on a large silver belt buckle. He has a fine head of hair, blond, curly, and carefully groomed. Were his teeth better he would be an exceptionally beautiful man.

It is not in my power to know the ultimate destinies of these new companions. Certainly I cannot perceive or even imagine that three of them will be totally abandoned by fortune, six will several times experience incredible fondling and protection by whatever fates dispense them, and even the indestructible Lester will one day succumb in such a prosaic affair that it would seem his doom had been merely postponed.

Within a week it becomes obvious that our path to advancement will be strewn with thorns. Lester proves to be a devil, with a genius for probing his pitchfork into our most tender regions. His remarks are scalding as he becomes better acquainted with our individual faults. They become the more wounding because they are so frequently true.

I am a favorite target since I am an idiot at hydraulics. I cannot seem to comprehend the innumerable relief valves or the exact function of each pump and line, much less draw the whole intricate labyrinth from memory as I am supposed to do. My private excuse is that the hydraulic system of an airplane is a mechanic's business and that if the landing gear or the flaps -- which the hydraulic system controls -- refuse to go up or down, then there is nothing I can do to effect repairs while actually flying.

I am equally thickheaded in the matter of engine theory and maintenance, perhaps because those engines previously responsible for supporting me aloft were of extremely simple design. They either ran or did not run; there was no compromise. In the latter situation you landed in the nearest corn patch. In spite of Lester's insistence that a pilot should be thoroughly acquainted with the complexity of a Wright engine, I have difficulty visualizing myself climbing out on the wing and performing any beneficial repairs while still in flight. There were to come certain times when I devoutly wished it were possible.

Lester's caustic and brutally frank dictum becomes for us a standard flowing in the wind. "I do not care if you kill yourselves, but the company will care very much if you kill any of our passengers. We need their business. Since once you are in the air there is no practical way of separating you from our customers, you will completely master the meaning of flight safety or you will never go near the line."

Such businesslike thinking is not too easily assimilated by some of us who have been more inclined to regard an airplane as a basically joyous instrument. When skillfully rolled, slipped, spun, and dived, a plane could provide endless delight if not a bountiful income. For us there was still enough glamour left in flying to relegate all monetary considerations far to the background. We did not begin to fly because we might make more money with an airplane than we might have if otherwise employed.

We are, almost without exception, in love. It is more than love at this stage; we are each bewitched, gripped solidly in a passion few other callings could generate. Unconsciously or consciously, depending upon our individual courage for acknowledgment, we are slaves to the art of flying.

There is already ample proof that this love is not a passing infatuation or merely a steppingstone to be endured until time brings another opportunity. The wedding is permanent. Many of us are barely able to afford shelter and three full meals a day; indeed, some are existing on borrowed money, or have sold their planes or whatever they possessed in order to manage through this training period. Yet we should each have been completely uninterested if the company had offered other employment.

Separation of the dedicated from the merely hopeful has been a crafty affair performed mostly by the line's chief pilots. They are braced with a fixed set of standards from which, in self-protection, they rarely deviate. They are hard, suspicious men, navigating uncomfortably between what is a frankly commercial enterprise and a group of fractious, often temperamental zealots. And since it is also their lot to be the first to inform a pilot's wife that she is now a widow, they do what they can to see within an applicant. They try to picture him a few years hence, when he may find himself beset with troubles aloft. How will he behave in sole command, when a quick decision or even a sudden movement can make the difference between safety and tragedy? Yet the chief pilots do not look for heroes. They much prefer a certain intangible stability, which in moments of crisis is often found among the more irascible and reckless.

While Lester berates and McIntosh humiliates, we are separated into groups of three and allowed occasional relief from their porcupine society. Four times a week we are permitted to lie with our bride and actually fly an airplane. It is mostly a serious reunion, although when unobserved we still manage minor caprices such as vertical banks, sideslip approaches, and so-called cowboy take-offs. These energetics are not accomplished in an airliner, for we have thus far only been allowed to stroll through one. Instead, we are provided with a single-engine cabin plane in which we are supposed to perform, in actuality, lessons learned in the classroom. As medical students work over a cadaver, we have assigned problems to complete, each pilot taking over in rotation.

Though accompanied by others who impatiently await their turn, a student pilot striving to master the technique of instrument flight and radio orientation may well be the loneliest man in the world. If his problem is ill performed the results are so painfully obvious that no combination of excuses can serve to forgive him.

"God may forgive you," Lester is fond of snarling, "but I won't."

In practice flights a single mistake is allowed to breed further mistakes, as it must do in reality. All but the final sum is realized. Even so, the notion of disaster, what would or could have happened, lingers; and the chastened pilot will not be so lonely again until some dreadful time a few years hence when the scenery and the situation are real and he may learn to pray hurriedly.

For weeks we follow the same routine. In the mornings we struggle with hydraulics, weather analysis, and paper problems flown in the Link Trainer. To the uninitiated this machine can rival the Chinese water torture. It is a box set on a pedestal and cleverly designed to resemble a real airplane. On the inside the deception is quite complete, even to the sound of slip stream and engines. All of the usual controls and instruments are duplicated within the cockpit, and once under way the sensation of actual flight becomes so genuine that it is often a surprise to open the top of the box and discover you are in the same locality.

The device is master-minded by an instructor who sits at a special control table. He can make the student's flight an ordeal. Godlike, he can create head winds, tail winds, cross winds, rough air, fire, engine, and radio failure. He can, if he is feeling sadistic, combine several of these curses at the same time. McIntosh, our usual instructor, is ever partial to such fiendish manipulations. When the flight is done and the student emerges sweating and utterly shaken in confidence, he will blandly point out that reality may one day treat him with even less consideration.

Some of us soon learn to hate McIntosh. Only much later will we recognize that his persecution is well intended and thoughtfully designed to harden us for what is true and inevitable.

While McIntosh appears easy enough with Lippincott and Watkins, who are more inclined toward engineering and mathematics, he is near despair with Gay, McGuire, and myself. His views on our potentialities as airline pilots are merciless and without subtlety. We are charlatans, flying clods, vastly overreaching our native capabilities. We belong back in some converted pasture, our empty heads adorned with helmet and goggles, our thoughts untroubled with the complications of bisectors, time-turns, localizer beams, and power graphs. Our temperaments are better suited to pure barnstorming or the happy-go-lucky, pseudo-romantic existence of a flying circus.

McIntosh does not know how he tempts us. For a return to such a familiar environment would now be so comforting. Still awkward and unconvinced when we cannot see, we reflect all too often upon the peculiarly sensual delight found only in open-cockpit flight. We remember summer evenings when the air was smooth, the deep satisfaction in a steep sideslip down to a field of soft green grass, the wings of a biplane slow-rolling around the dawn horizon, the thrumming of flying wires in a dive through a break in the clouds, and the strangely pleasant odor of wood and shellacked fabric, of which our airplanes were made. All that is gone now. Like sailing-ship men, what we have left has already begun to disappear forever.

A shrewd observer would know that our troubles in the school are circumstantial and therefore meaningless. We are students, but not boys. We already know what it is like to be responsible for the lives of others; indeed, few men suffer and fret like an itinerant instructor watching a student make his first solo flight. We simply cannot, as yet, conceive of the heavy responsibility to which we pretend. McIntosh's efforts to sober our thinking only expose our tempers and reveal a shameful lack of discipline.

Even so, a change falls gradually upon all of us. The early anxieties and raw-edged nerves have disappeared by the time our afternoon flights are flown over an earth which is also changing. The snow of the winter, which always makes the fields and villages below appear like perfectly executed scale models, is gone. Now from aloft the fields seem dead and unyielding, yet every patch of forest and the lands bordering the muddy streams are gently touched with a seemingly weightless powder of green.

In the beginning of spring we are more certain of ourselves, and even Lester occasionally manages to maneuver his broken features into what could pass for a smile. Gay talks of marrying a girl from his home town once he is firmly established on the line. Lippincott, more effervescent than ever, waits impatiently for his actual assignment to one of the several possible bases. He is the star of our group and will doubtless be first to leave. Watkins still plays the clown occasionally, but his trickery is more intricate and assured. He delights in baiting the funereal McIntosh with such welcome diversions as pretending to have a fire in the Link Trainer. He reminds us that there is such a thing as laughter. McGuire seldom mentions his mythical, though much-loved mule.

Sisto, as incorrigible as ever, his roguish mind constantly alert to every possible advantage, has discovered the factor of seniority. He is distressed that so few of us seem to appreciate its importance. We are uncomplicated innocents in love with our work and totally preoccupied with finding a place on the line. It never enters our heads that a simple number can send us flying over lands we have never heard of, leave us to languish in boredom, or even chop off our lives just as they have truly begun to flourish.

All airline pilots are subject to the high cock-o-lorum of seniority, whether they like it or not. The system was established to banish favoritism and to provide some basis for assignment of bases, routes, flights, and pay. Its great fault, as in any seniority system, is the absolutely necessary premise that all men are equal in ability. The dullard and the genius must both live with the ostrich philosophy that one man can fly as skillfully as another. No one, of course, maintains this to be a truth. But the seniority system must ever persist if only because it is a protection of the weak, who are everywhere in the greatest number.

The ambush of evils crying seniority is always lurking near any man who must live with the system. It can make little, half-fearful automatons of men who, in their own milieu, might have the fire for greatness.

We are not yet aware of this. In our eyes the line pilots stand very close to heroes. Sloniger flew with Lindbergh. Coates won a medal for bringing a blazing ship to earth without harm to any of his passengers or crew. Cutrell was a pioneer in blind-landing experiments. Vine and McCabe flew the mail in open cockpits, as did DeWitt, Kent, and Hughen. Bittner was a part of Gates's famous flying circus. We cannot wait to serve such men as copilots.

By the time the green froth of the trees below has become a solid coverlet and the hardness is gone from the sky, we are considered ready for assignment to the line.

"Now that you are about out of my hair," Lester says, to his usual accompaniment of cracking knuckles, "I wish you luck. So much for sentiment." He purses his lips together until they are nearly invisible, and there follows another series of cracklings which sounds like a man building a small fire.

"Just do what your captains say in the air and stay out of trouble on the ground. This combination will keep you alive and also eating."

We do not depart from the school in a body. We dribble away singly and in pairs as the various bases express need of new pilots. Gay is sent to Memphis, which delights him. We will not see each other for over two years and then under the most peculiar circumstances. And after that meeting -- never again. Mood is sent to Nashville, and I am happy for him since our original antagonism has suddenly reversed itself and we have become fast friends. I will one day hear his voice aloft very far from this place, plaintive but still courageous under the most frightening conditions. Watkins, handsomer than ever in his new uniform, is sent off to Boston. We are destined to survive several adventures together -- except his very last.

McGuire remains in Chicago. In the curiously shy handshake of our parting there is no suggestion that our fortunes will be intertwined and lead to a situation in which McGuire's luck will very nearly collapse entirely.

Owen is assigned to Newark, and Carter to one of the southern bases. He growls a farewell and, with his new uniform cap tilted rakishly, lumbers off, already thumbing his nose at petty interference with his aims. He will one day prove himself a very brave man, hugely sentimental if not always discreet. Charleton, sadeyed and quiet as ever, is sent to Cleveland, a prosaic enough beginning for his heroic end.

I am also sent to Newark. Shortly after arrival, I am given the seniority number 267. Mood in Nashville is given 268, and Gay in Memphis captures 260. The differences we consider inconsequential, for our positions are so far down the list that we feel we could never achieve a captaincy in our lifetimes.

Thus we separate, our spirits as bright and untarnished as the one and one half stripes of gold braid on our uniforms. We are too old to have formed the youthful friendships of schoolboys, yet we are bound forever by the unbreakable numbers.

Copyright; 1961 by Ernest K. Gann

Customers also bought

Product title

Vendor

$19.99 | $24.99

Product title

Vendor

$19.99 | $24.99

Product title

Vendor

$19.99 | $24.99

Product title

Vendor